Leopard Sharks

As ocean temperatures get warmer Leopard Sharks aggregate in the waters of southern Queensland and Northern New South Wales.

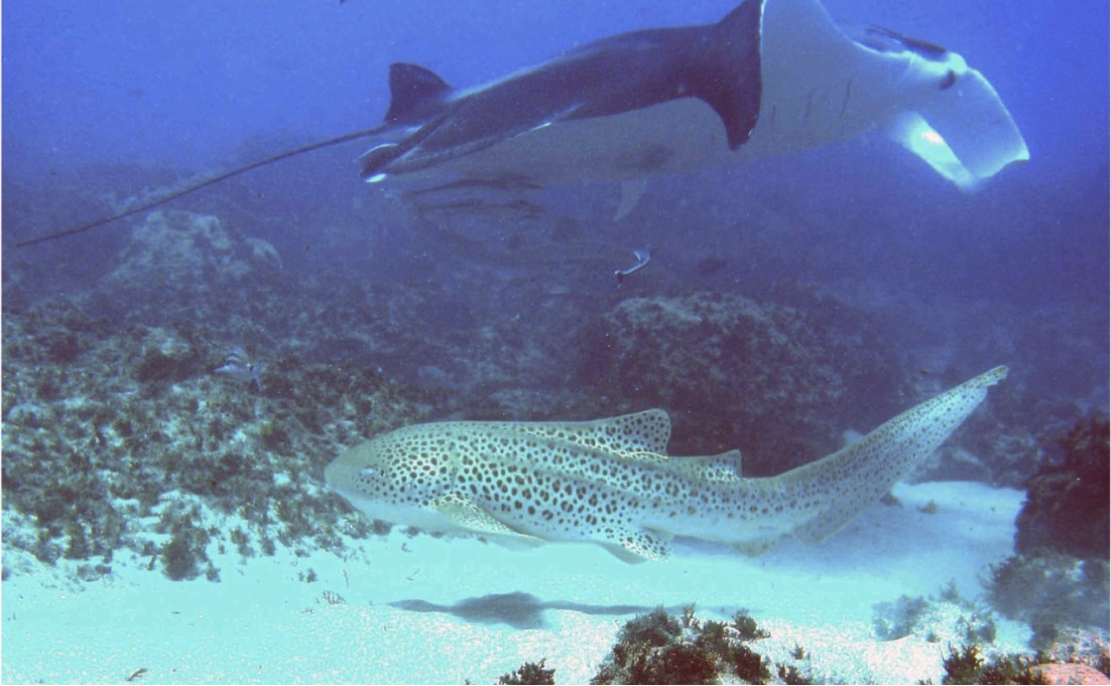

Shark. That very word strikes fear into the hearts of us. Their size, power, and great, toothy jaws fill us with fear and fascination. Enter the leopard shark. It is far from frightening, is not aggressive towards humans, and spends most of its time slowly cruising the seabed, quietly searching for food.

As the temperatures get warmer, mature adult leopard sharks aggregate in the waters off southern QLD and northern NSW over the summer months every year.

According to Dr Christine Dudgeon from the University of Queensland, the longest and most comprehensive studies of wild leopard sharks have been conducted off Nth Stradbroke Island.

“Currently 388 individual leopard sharks have been photographed and identified off the dive site known as Manta Bommie/The Group, at Nth Stradbroke Island.

“Each shark is identified by its unique distinctive markings and approximately 460 adult leopard sharks aggregate in this region every summer, the largest known gathering in the world,” Dr Dudgeon explained.

They are a largely mysterious species of shark, and have some interesting characteristics. As hatchlings, leopard sharks have distinctive black and white stripes – and during this stage are often referred to as zebra sharks. These break up into spots as the shark grows and the stripes disappear by the time they are a year old. It takes two years for them to grow to 1.6 -1.8m long when they then become sexually mature. By this time they have developed unique spotting patterns which can be used as fingerprints to identify individuals. The largest sharks reach about 2.5m in total length, with almost half of that being tail.

These sharks spend a lot of time on the bottom of the ocean on the sand feeding mainly on snails, crabs and small fish. They can pump water over their gills through their mouth which enables them to breathe while stationary, similar to stingrays and other bottom dwelling sharks. In contrast, white sharks, blue sharks, bull sharks and manta rays have to swim to breathe.

Uniquely, the female leopard shark has the ability to clone itself. In one example, a female in isolation in an aquarium started laying eggs. Egg laying sharks will lay unviable eggs (like chickens) if not fertilised; however several of her eggs developed embryos and of these, four survived as hatchlings and adults. Genetic analyses showed that the babies had the exact same genetic signature as the mother indicating that they are clones of the mother.

“Using acoustic telemetry, studies show that leopard sharks visit southern Queensland primarily during summer and particularly when water temperatures rise above 22 deg Celsius.

“Current studies are examining migration of leopard sharks, and preliminary results show that sharks tend to move north in the waters of Fraser Island and the southern Great Barrier reef. One shark was shown moving all the way to Cairns and back (approximately 2600km) in a six month period.

“There are currently 18 leopard sharks being tracked with acoustic telemetry (tagged off Nth Stradbroke Island) off the east coast of Australia at the moment,” Dr Dudgeon explained.

These exquisitely marked animals are classified as Vulnerable to Extinction on the IUCN Red List – the same listing as polar bears and great white sharks. Leopard sharks are fished for fins, meat and skin in the shallow coastal waters of the Indo Pacific region from South Africa to Fiji.

Where can you see them? In the summer months if you stand on the Main Beach headland you may see them passing by surfers in the Main Beach line up, or perhaps snorkelling off Deadman’s Beach or Manta Bommie.

Sincere thanks to Dr Christine Dudgeon, Post-Doctoral researcher at the School of Vet Science at the University of Queensland for her assistance and photograph , and to John Gransbury for his photographs.

Article by Angela McLeod

Photograph on next page by Christine Dudgeon