FOSI Newsletter Issue #77 September 2017

In this issue

Facebook Activities

- Newly Discovered Land Snails from North Stradbroke Island

- Launch of FOSI's Nature Guide

- Glossy Black Cockatoo Count Report

- Brown Lake

- Red Lake

- Facebook Activities

Newly Discovered Land Snails from North Stradbroke Island

By Dr John Stanisic, Honorary Research Fellow, Queensland Museum

Land snails were first identified on North Stradbroke island by natural scientists some years ago.

They are rarely seen but are nonetheless critical components of the island’s natural environment. Large mainland species such as Fraser’s Banded Snail, Pale Banded Snail and the Greater Brisbane Woodland Snail are found in many of the island habitats which range from rainforest through eucalypt woodland to heath. However, very little scientific attention has been directed at the tiny species collectively known as the Pinwheel Snails.

Dr Stanisic at work in the Queensland Museum, Photo by Mary Barram

Pale Banded Snail

Fraser's Banded Snail

Minjerribah Pinwheel Snail

Myora Pinwheel Snail

Greater Brisbane Woodland Snail

Snail photos by Dr John Stanisic

Pinwheel snails are a highly specialised group of land snails in eastern Australian forests. With an estimated 750 species (many yet to be named) this group of land snails is typically characterised by shells which are very small (1.5- 5.0 mm in shell diameter), shaped like circular discs and prominently sculptured. Most species show fidelity to very small patches of scrub resulting in high local endemism – the entire species is found living in only one small area.

The natural history of North Stradbroke Island-Minjerribah has recently been the focus of a wonderful publication highlighting the island’s unique wildlife and ecology (‘A Nature Guide to North Stradbroke Island-Minjerribah’). Featuring many of the island’s terrestrial vertebrates (mammals, birds, reptiles) this nature guide only gave limited exposure to the many invertebrates which form such an integral and pivotal role in the island’s natural environment.

Insects (dragonflies and butterflies) carried the baton for the myriad of ‘spineless’ creatures that inhabit the forests of North Stradbroke Island-Minjerribah. Recent discoveries of new land snails unique to the island serve to stress the importance of these comparatively tiny species to ecological processes and healthy environments.

Two species of pinwheel snail have recently been described from very different habitats on North Stradbroke Island-Minjerribah. The Myora Pinwheel Snail was first described in 2010 from rainforest habitat (microphyll/notophyll vine forest) at Myora. In contrast the Minjerribah Pinwheel Snail was described from the island’s widespread Scribbly Gum and Blackbutt forest habitats in late 2016. These species are tiny (mean diameters 4.82 mm and 2.46 mm respectively) and are considered to be endemic to North Stradbroke Island-Minjerribah – that is they are found nowhere else on earth.

In general, the presence of native land snails (as opposed to the many introduced snails and slugs that inhabit most backyards) indicates a healthy environment. The added occurrence of the tiny pinwheels is a further endorsement of a thriving and functioning ecosystem.

Land snails are invertebrates and as such part of that other, not insignificant 99% of terrestrial animal biodiversity. Invertebrates rarely get the recognition they deserve for the work they do in keeping the ‘engine room’ of an ecosystem ticking over.

Without them and the many of the key functional roles they play in the environment (soil building, predation, decomposition, pollination), the larger life forms including Homo sapiens, would cease to exist. Land snails form 6% of terrestrial animal biodiversity worldwide, second only to the insects and Australia has an estimated native snail fauna of 2500 species that are important contributors to the decomposition process in the ecosystem.

They feed mainly on fungi and micro-algae converting these into protein which can provide food for other animals such as birds, small mammals, lizards, beetles and even some snails. They also nutrify the soil through their faeces and decaying bodies, while their dead and decomposing shells provide an additional source of calcium in the environment.

Snails are nocturnal and go about their lives in virtual anonymity far from the eyes of most humans. They live in the litter zone, usually under logs, rocks and other forest debris, emerging mainly in times of high humidity such as early evenings or after rain.

Noisy Pitta - Snail predator, photo by Angus McNab

Most of our native species, including those named above from the island, are pulmonates (lung breathers) and hermaphrodites (possessing male and female reproductive organs). When they mate they cross-fertilise rather than self-fertilise. As a result both snails of the mating pair have the ability to lay eggs which among the larger species normally number 10-20 per clutch.

Multiple egg-laying events can result from a single mating because they have an internal organ that can store sperm for some time after mating. This can lead to a rapid build-up in snail numbers after periods of drought which usually result in population decline. Land snails are estimated to live between 5-15 years depending on circumstances.

Apart from predators, desiccation from drying out is a snail’s worst enemy. A land snail must constantly secrete mucus during activity periods (both for forming the snail trail that it needs to crawl on and for keeping the body moist) and as a result can lose a significant amount of moisture. This can lead to stress and ultimately death for a snail operating in a really dry environment for any length of time.

To cope with extended dry periods and for life in semi-arid and arid areas of Australia, snails employ a strategy of aestivation (snail hibernation). During aestivation a snail will usually seal to an object such as a log or rock, lower its metabolism and wait for the next rain event before activating once more.

Some snails will lie free in the soil but cover their aperture with a heavily calcified shield known as a epiphragm.

Predators of snails are many and varied. Among vertebrate animals the most notable is the Noisy Pitta which visits North Stradbroke Island each winter. This rainforest bird, sometimes spotted at Myora and in Point Lookout gardens, inhabits the forest floor where it seeks out snails and breaks their shells open on a rock (anvil) or other hard objects such as discarded beer bottles.

However, there are also carnivorous snails among our native species which feed on invertebrates such as earthworms and snails including members of their own species-which is why they are sometimes referred to as cannibal snails!

North Stradbroke Island-Minjerribah has a robust native snail fauna reflecting the complex environments present on the island.

The discovery of the two endemic pinwheel snails (and there are others still to be named) identifies this snail community as unique in the context of the eastern Australian land snail fauna - and another very good reason to protect this special island.

Launch of FOSI's Nature Guide

Finally, after our first attempt to launch FOSI’s A NATURE GUIDE TO NORTH STRADBROKE ISLAND- MINJERRIBAH was cancelled due to Cyclone Debbie in March, we held a most successful event at Avid Reader bookshop in June. FOSI members, supporters, contributors and photographers attended, crowding the space with about 100 people. Everyone enjoyed the evening and meeting other Straddie lovers. Avid Reader is one of our best retailers and Fiona Stager hosts all Brisbane’s best book launches!

We were lucky to have Dr Kathy Townsend, Director of the University of Queensland’s Moreton Bay Research Station, perform the honours of officially launching FOSI’s new book.

Kathy assisted us with the Life in the Ocean chapter and spoke brilliantly about the need to protect the wonderful marine ecosystems of Moreton Bay. Her work analysing the effect of plastic ingestion on turtles in the bay has contributed to the planned laws banning single use plastic bags in Queensland. Thank you Kathy.

Another speaker was Margaret Grace, a long-term FOSI member and an old friend of Jani Haenke and one of the Trustees of her Charitable Trust. Margaret spoke affectionately about Jani’s life and work for the island’s environment as well as her great interest in the arts. She explained the work of the Trust in allocating money (now complete) to many different causes close to Jani’s heart. We thank Margaret and Jani’s sisters Angela Geertsma and Margot Salmon, as well as Trustee, Tony Bennett for their assistance in providing the funding for the book.

Sue Ellen and Mary, contributing editors, had quite a bit to say about the rationale and process of writing and publishing the book. Mary discussed the history of the book and how involving so many island nature lovers and explorers, photographers and scientific experts made the book into a real community project.

Sue Ellen spoke about the ideas behind the book and how it is an important element of FOSI’s objective to preserve the natural world of Stradbroke. They both also acknowledged the great work of Michael Phillips (the book’s talented designer), Susan Hill (the skilled and careful technical editor) and the very knowledgeable Tim Page (the book’s scientific editor). Susan got to know the island so well she was inspired to join the FOSI committee this year.

Glossy Black Cockatoo Count Report - May 2017

FOSI member, Margie Barram, volunteered on behalf of FOSI to look for Glossy Black Cockatoos on the island for this year’s count held in May. Here is her report to the Glossy Black Conservancy which organised the count:

‘I visited three island areas, and in each area looked for chewings (orts) beneath she-oaks I encountered, and for Glossy Black Cockatoos. My findings at the three areas were as follows:

1. 11 am to 1:15 pm: Brown Lake - I walked the hill-side behind the children's playground, and around the shore in Brown Lake area 1; I walked the road to Brown Lake area 5 and checked for chewings in the she-oaks adjacent to the road; I walked up the closed-to-cars track from Brown Lake area 5 to the crest of the hill, and checked for chewings in the she-oaks adjacent to the road. I didn't see any Glossy Black Cockatoos; I didn't find any chewings.

2. 1:30 pm to 3:30 pm: Dunwich Gold Course - I introduced myself to the guy on in the club house and got permission to be on the golf course. He said the golfers report seeing Glossy Black Cockatoos in the lower fairways [where the land dips down away from the upper fairways] and pointed me in the right direction. Ron, a golfer I passed on my return to the club house, said he had seen them very often in April, in a large old Acacia near Tee 6. I didn't see any Glossy Black Cockatoos, but I did find chewings at three trees. as follows;

2.1 Forest she-oak - a tree between the two fairways, 50 m downhill from the forest she-oak opposite the local rule sign 5/14.; the orts were fresh [brown]

2.2 Black she-oak - a tree 20 m in on the side track from the fairway to the windmill [& bee-hives]; on the left as you walk towards the windmill; the chewings were fresh [brown]

2.3 Forest she-oak - a tree, 10 m from the windmill, on the left-hand side of the track leading to the windmill; the chewings were fresh [brown]

3. 3:45 pm to 5:15 pm: Beehive Corner - I said hello to the man at the house. He said Dave was away, and he was just there for the day - so I didn't get a chance to ask Dave if he had seen the birds recently. The drizzle increased to light steady rain, and no birds came for a drink when I was there. Sunset was set for 5ish; last light for 5:30ish for Straddie, but by 5.15pm it was getting too dark, given the rain, for me to clearly see much at all. I didn't see any Glossy Black Cockatoos. Perhaps the birds don't need a drink on a wet day?’

So sadly, no cockatoos were sighted this year (unlike last year) but Margie commented that she had a good day out, in beautiful bush and maybe she'll have better luck next time and actually see one!

FOSI is a supporter member of the Glossy Black Conservancy and its work highlighting the needs of these special birds.

Brown Lake

Anyone familiar with Brown Lake who has visited recently will have been quite shocked at just how low the water level is. This is the largest lake on the island and fits the criteria of a perched lake, sitting around 20m above the water table and retaining rainfall and runoff by way of a layer of cemented organic matter, laid down over thousands of years. In times of severe drought water levels in the lake have been known to drop drastically, so is the weather to blame?

Understandably there has been considerable speculation about the effect on island lakes of pumping of enormous quantities of water for Redland’s water supply. In addition, a greater quantity of water is extracted for use in the sand mining processes. This water is not pumped off the island but does not return to its exact source and could be lost unnaturally to the sea and via evaporation. There is no doubt that there is a lack of public transparency and probably inadequate government oversight of the sustainability of water pumping on the island. But the isolation of perched lakes from the main aquifer probably rules out extraction for dropping water levels at Brown Lake.

There are reports of low water level at other perched or fluctuating water bodies. Swallow Lagoon is down as is Welsby Lagoon and Tortoise Lagoon along the walking track to Blue Lake, appears completely dry.

Dr Kathy Townsend, Director of the UQ Moreton Bay Research Station, has taken a scientific approach and looked into the most obvious cause – the weather. Kathy came up with rainfall and temperature graphs for the last 10 years at Dun

wich which she has kindly passed on to FOSI. They tell the story, particularly over the past few years, of lower total rainfall, fewer consecutive days of rain and higher average temperatures compared with recent past records.

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology and NASA have stated with certainty that the world is experiencing consistently higher temperatures and more extreme weather events. North Stradbroke Island as an environment of sand and water is experiencing many pressures – global warming seems to be one that is revealing itself as a problem already. Our friends from FIDO (Fraser Island Defenders Organisation) are reporting evidence of effects on that island too. The solutions to preserving these sand islands’ delicate environmental balance are not just local but global as well.

Article by Sue Ellen Carew, graphs by Dr Kathy Townsend

Red Lake

We are used to our lakes on Straddie being named for their colour, but little did we expect that we would be presented with a brand spanking new lake that’s RED!

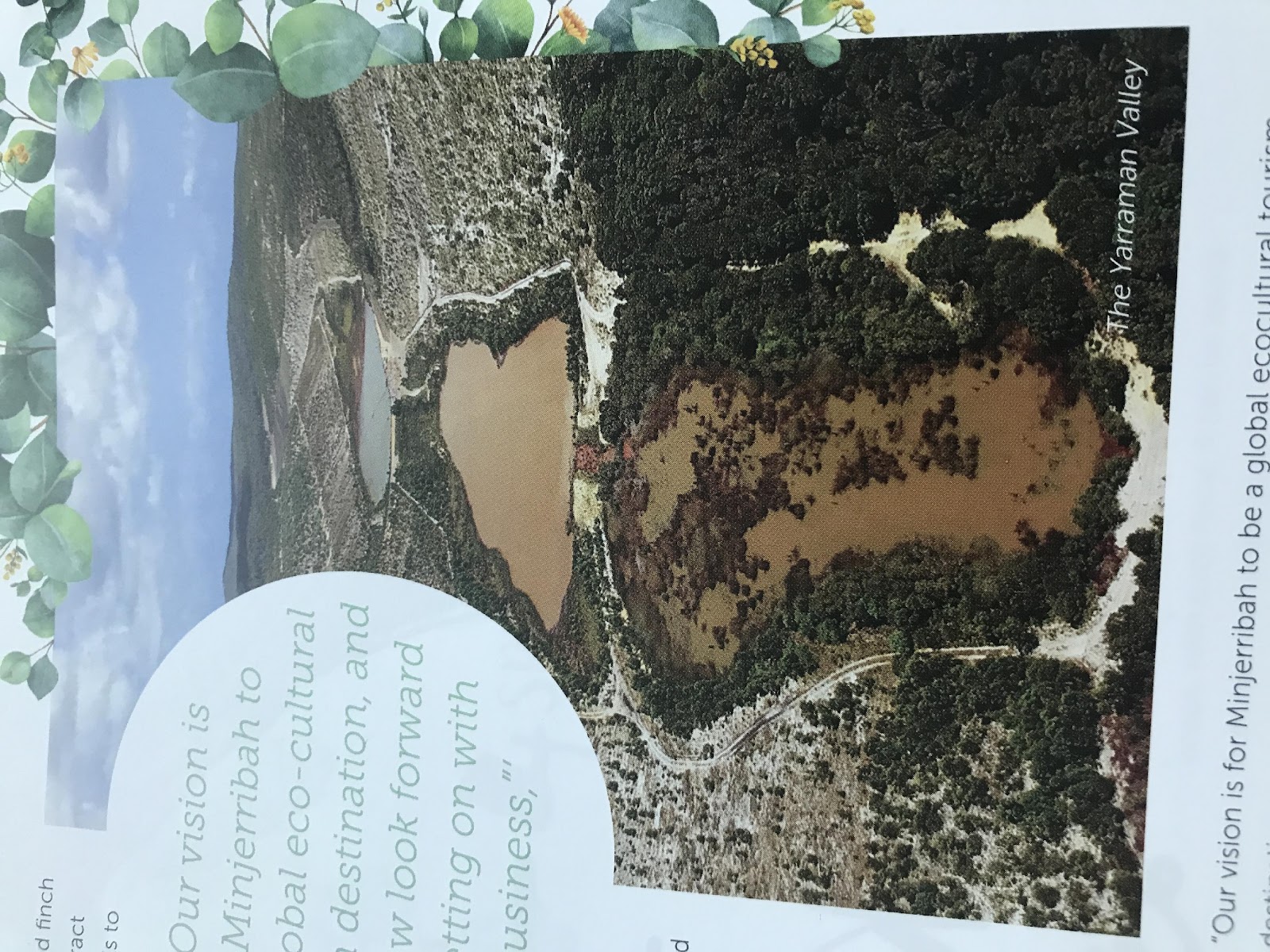

All-seeing Google Earth reveals that for the past year one of the two major artificial ‘lakes’ at the Yarraman Mine rehabilitation site has transformed from a garish unnatural aqua colour to a deep red. An explanation has been provided by the Belgian mining company, Sibelco, slipped into what is obviously a puff piece in the local Straddie Island News (SIN) Winter issue. Amongst claims that rehabilitation is proceeding in an orderly manner to undo sins of past rehab attempts in order to create a “two kilometres long…restored valley…the largest wetland and valley in South East Queensland, if not Australia” is the statement:

“Over the next six months we’ll be focusing on establishing wetlands and monitoring water quality, which includes monitoring iron levels in the Yarraman Valley. There are also plans to remove the final sand wall, which will only occur when the required water quality results are achieved. This will allow water to flow unrestricted throughout the valley and restore it to its original condition.”

Note the reference to 'iron levels', presumably a reason for the red coloration of the water.

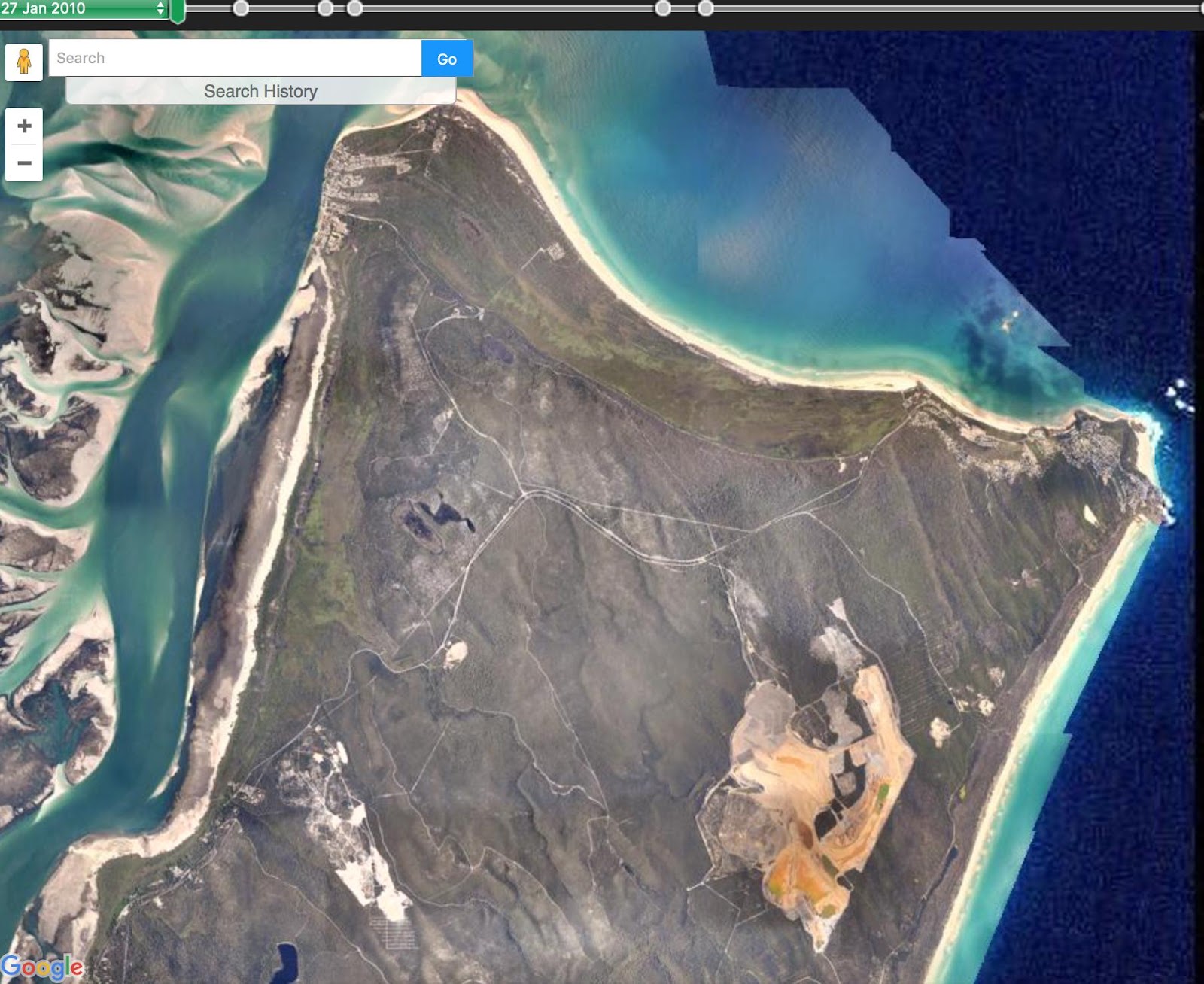

As the 2010 Google Earth image reveals, the “original condition” contained NO water-bodies. Best practice mining rehabilitation requires that mining voids be filled in and areas restored as far as possible to pre-mining topography and vegetation patterns. The huge water-filled mining void planned by Sibelco obviously does not comply.

The image of the ‘Yarraman Valley’ accompanying the SIN article is designated as “courtesy of Sibelco”. Funnily no Google Earth images nor any historic or recent aerial photos in FOSI’s possession reveal such an image. Have a look at the image of the lakes in the April FOSI newsletter. We do query whether the image is some sort of photo-shopped confection to give us delight and hope as we read the fine words about the island’s wonderful natural attributes and all the people doing their best for the island.

Rather than set people’s minds at rest about what is happening at the former Yarraman mine the SIN article, in our view, prompts only doubts and questions.

No waterbodies were present in the area in 2010

Sibelco's photo from SIN article June, 2017

Distance photo of google earth image April 2017

Facebook Activities

Facebook and other social media are setting the agenda for environmental issues.

FOSI has very recently embraced this trend with our own badged Facebook page Friends of Stradbroke Island- Minjerribah-Nature Guide.

The page is designed to complement our Nature Guide and to “Celebrate the island’s natural beauty and wildlife through the seasons for all to enjoy.”

The FOSI page also has a handy ‘Shop’ to purchase copies of the Nature Guide.

Toondah Harbour is being resisted by a number of community groups in the Redlands. You can add these facebook pages to your likes and follows. To follow the Toondah issue (and Straddie too) go to Save Straddie

And check out Save our Bay Toondah Harbour and Toondah Friends. The Redlands 2030 website has much information under its ‘Toondah Harbour’ tab.

Also recommended is a wonderful nature photography Facebook page - Wild Redlands with Chris Walker -for great, mostly bird, photography, especially the migratory and resident shorebirds around Toondah Harbour.

Have you considered making a donation to support FOSI’s work?

Friends of Stradbroke Island relies on the generosity of our members to fund our work. All donations made to the Environment Fund are tax deductible. It is easy and secure to make a donation by bank transfer (ask us how). Your donation will help fund our ongoing public information and education campaigns and support relevant scientific research affecting North Stradbroke Island on issues such as environmental damage caused by land clearing, sand mining, hydrological changes, plastic and feral animals.